📦Scalable Android App Architecture with Jetpack Compose

● 03 Jul 2024

Working as a mobile developer, you’ve likely encountered the challenges of a complex app, an entangled codebase, and a continuously growing team. Each new feature feels like adding blocks to a Jenga tower that might topple over at any second. And it is not only you, there are many of your colleages trying to do the same in your team or even other teams trying to put a block to your tower and destroying it unintentionally.

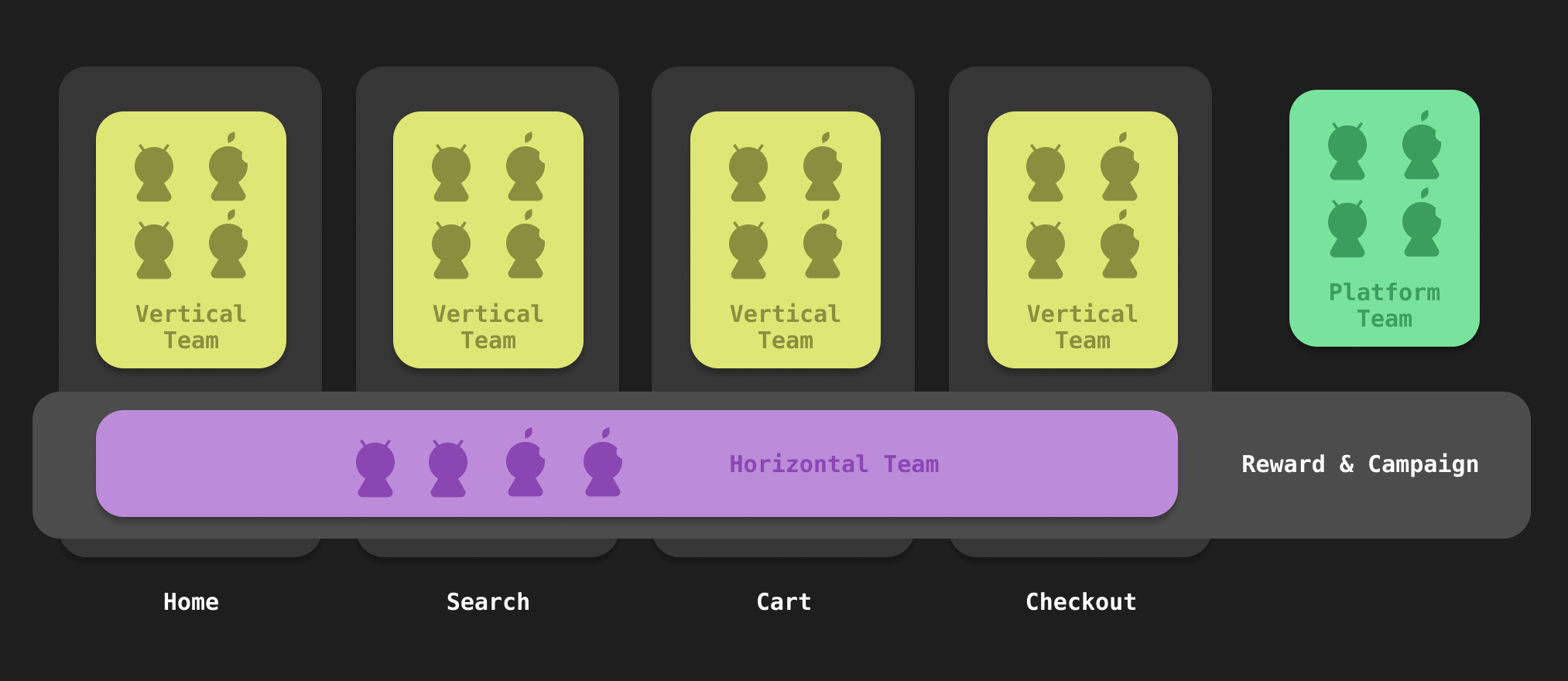

Scaling Mobile Team

When a company grows, a single mobile team may struggle to deliver features quickly enough. To address this, companies often hire more engineers to take care of separate parts of the app. These teams typically fall into three categories:

- Vertical Teams: These teams focus on specific screens or features within a screen. They own the entire development process for their assigned features, from design and implementation to testing and maintenance.

- Horizontal Teams: These teams focus on specific domain that spread across multiple screens. For example, a “Rewards Team” might handle integrating promotional features across food delivery, taxi, and shopping screens.

- Platform Teams: These teams focus on solving platforms technical problems such as performance, infrastructure, and CICD.

This doesn’t sound bad but the following issues can arise between vertical and horizontal teams:

- Limited Collaboration: Teams may not collaborate enough. Changes by horizontal teams can break functionalities or miss context owned by vertical teams. This necessitates thorough code reviews and discussions.

- Unclear Ownership: Sometimes, code from horizontal teams needs to be integrated within vertical team code for functionality. This can lead to confusion about ownership and responsibility for maintenance or bug fixes.

- Human Error: Even with close collaboration, mistakes are inevitable.

What if we could fix this by using an architecture.

Architecture

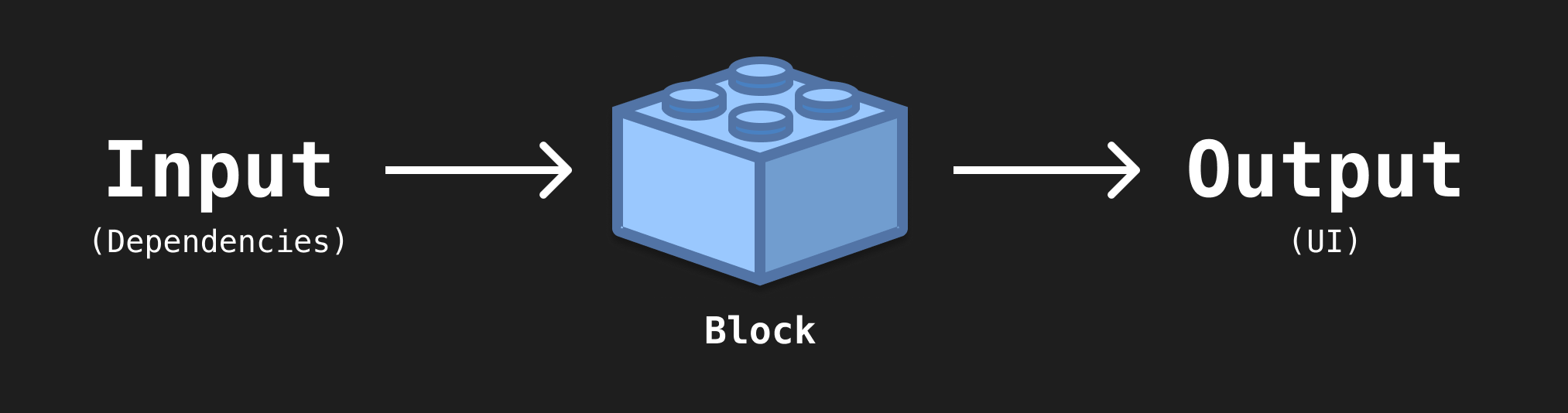

Instead of looking at the screen as a whole, we can break it down into smaller, independent parts. This allow different teams to own these parts, aligning with the organization’s structure and adhering to Conway’s law. Declarative UI frameworks like Jetpack Compose make this decomposition much easier than before. From here, I’ll refer to these screen components as “Blocks”.

A Block has clear input and clear output.

- Input is the dependency. What do you need in order for Block to process and return output.

- Output is the User Interface. This could be one Fragment or Composable component.

Here is an example of a Block implementation.

class ShoppingCartBlock(input: ShoppingCartDependencies) {

...

val output: @Composable () -> Unit = {

// Jetpack Compose Component

}

}

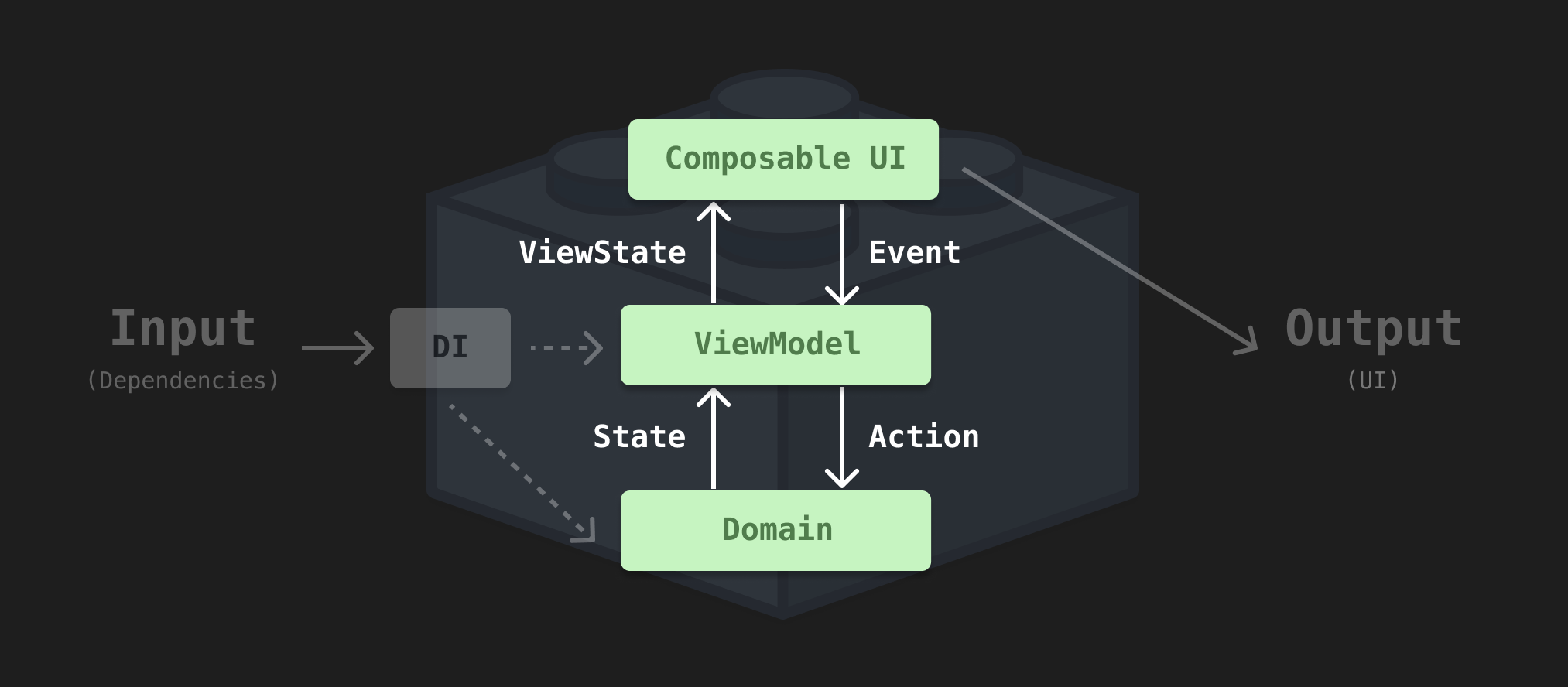

Block is pattern-agnostic, which means it is up to the team to choose what pattern to use. For example, it can be implemented with MVVM(Model-View-ViewModel)

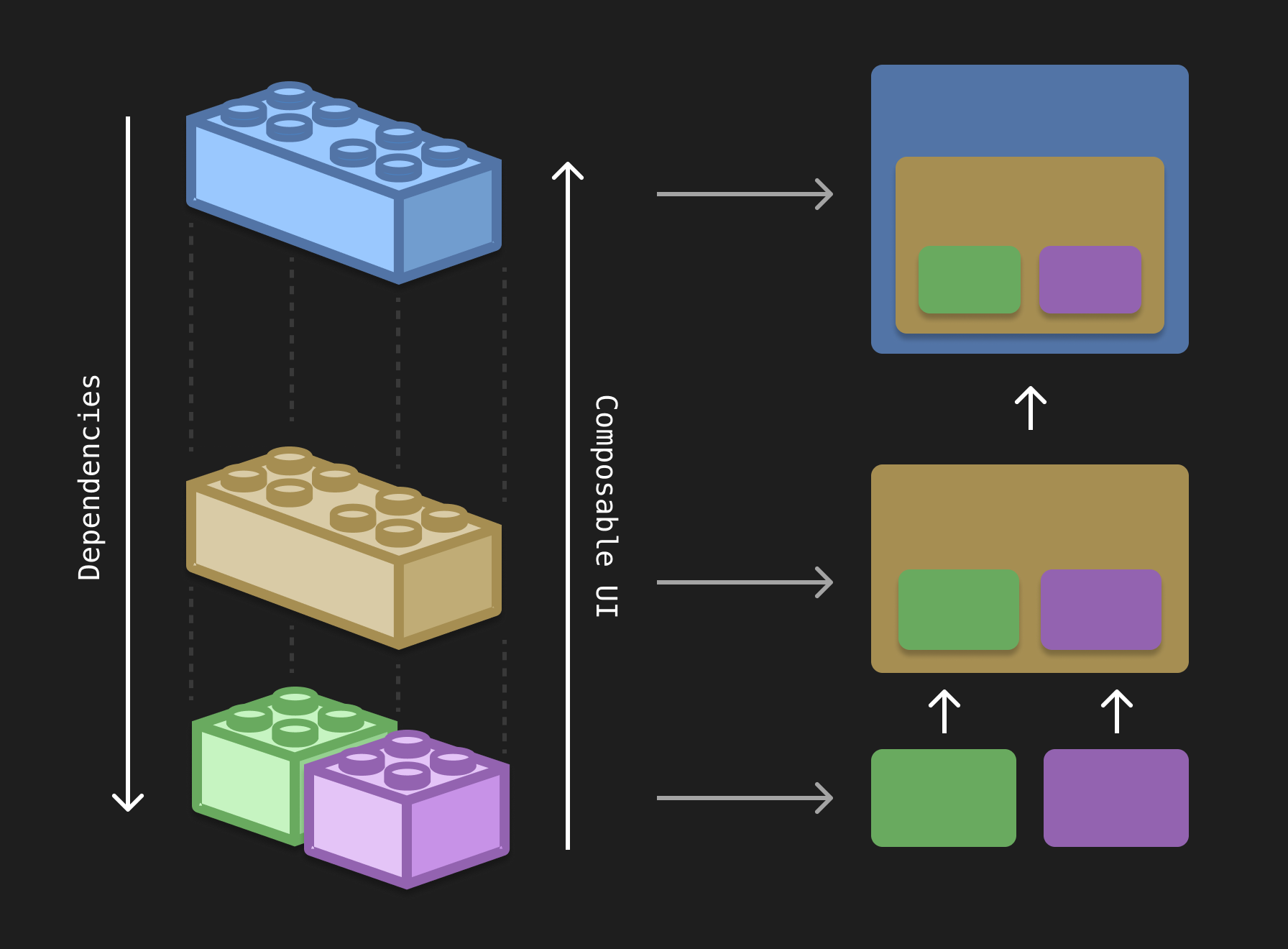

Blocks then can be connected together to form a single UI screen. Let’s look at this example UI component which consist of many parts. Each of them could be produces from different Block and owned by different team.

Coming back to the Shopping screen. If the screen consists of two parts, Shopping cart and promotion input. We could implement promotion MVVM Block like this with Dagger as Dependency Injection framework.

class PromotionBlock(input: PromotionDependencies) {

private val component by lazy {

DaggerPromotionBlockComponent.Factory()

.create(input)

}

val output: @Composable () -> Unit = {

val viewModel = component.viewModel

PromotionUIComponent(viewModel)

}

}

Inside ShoppingCartBlock, we can add PromotionBlock as a child Block by initialize the Block and use its output component.

class ShoppingCartBlock(input: ShoppingCartDependencies) {

private val component by lazy {

DaggerShoppingCartBlockComponent.Factory()

.create(input)

}

val output: @Composable () -> Unit = {

val promotionBlock = PromotionBlock(component)

ShoppingCartUIComponent(

vm = component.viewModel

promotionSlot = promotionBlock.output()

)

}

}

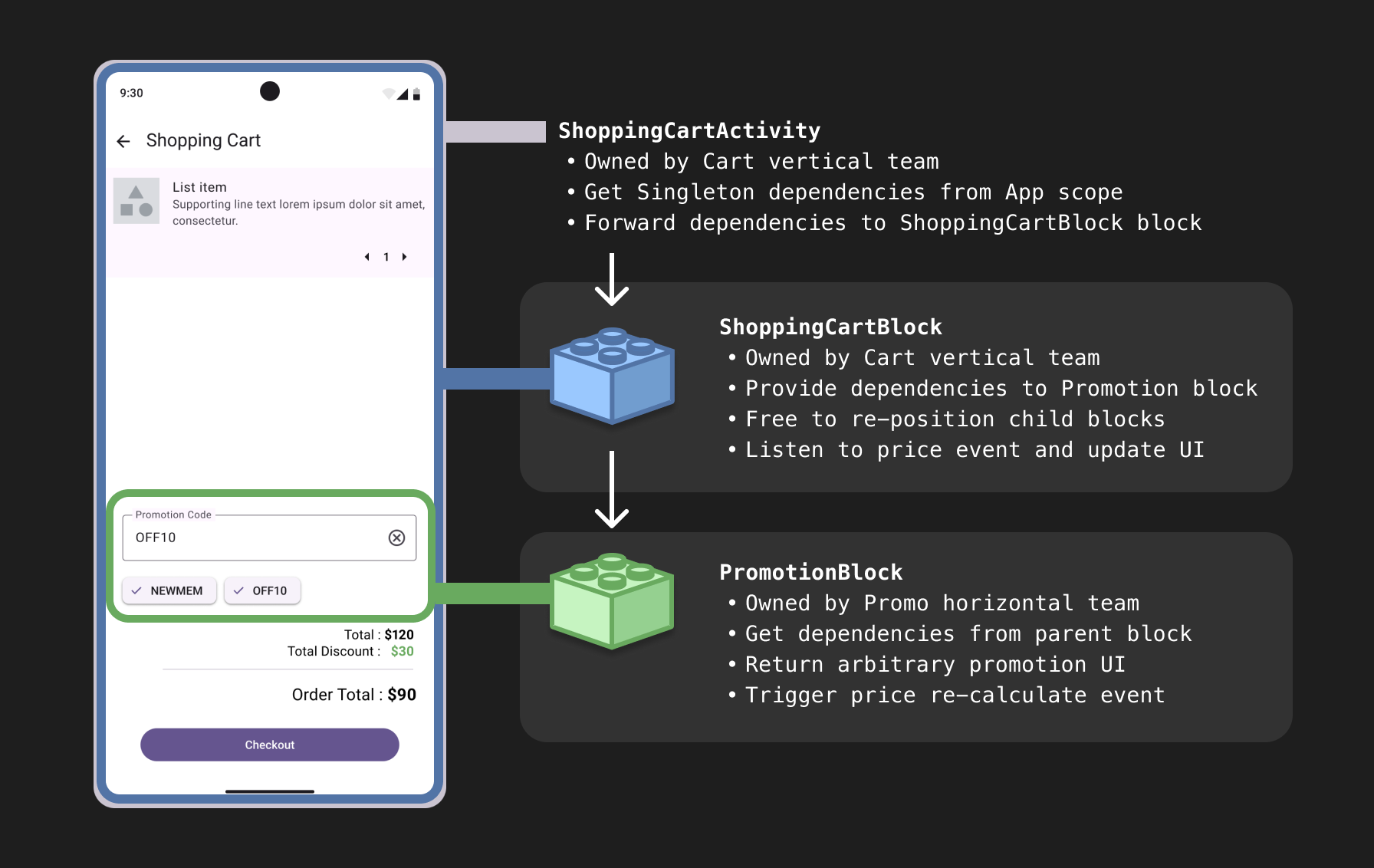

Now, let’s reivew the current Block tree

If the app is not SPA(Single-Page-Application), the top most Block will get the dependencies from Activity, and then forward required dependencies to its child block(s). For instance, the Promotion Block.

With Block Architecture:

- The boundary between teams is clearer, reducing the communication gap and context mixing.

- Each block can be put into its own module, simplifying ownership declaration and promoting maintainability.

- Passing down dependencies from another team’s parent Block requires communications between the team (Dependency changes will require parent Block’s team to review the PR).

- Block only cares about input/output, so each team can decided on their own architecture pattern and conventions.

Conclusion

With modern declarative UI frameworks, this idea could be implemented on Android and even on iOS using SwiftUI. You can achieve scalable mobile application architecture without having to use third-party library at all which reduces the learning curve for new team members and minimizes the amount of “magic code” the team will have to understand. You can access the full demo here «WIP».